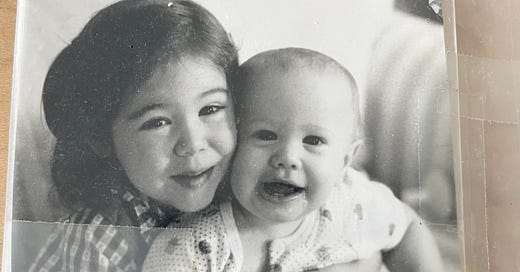

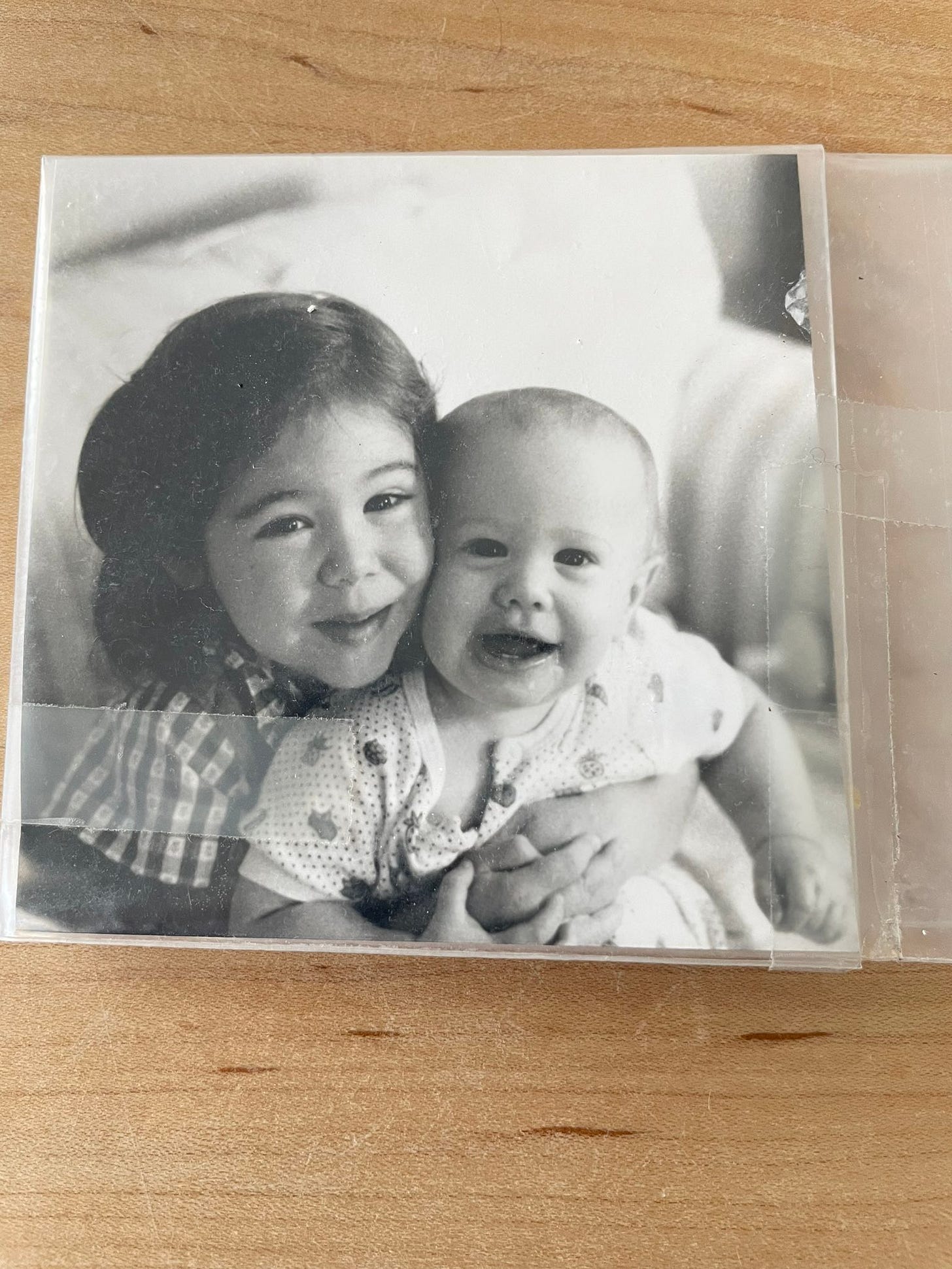

Last week, my mother sent me a box of photos, a little bomb in the mail. Most of the photos from my childhood were lost in the fire, but my parents also have nine storage lockers, so I assume some of the photos came from there. She wants me to forgive my brother for burning the house down, so a lot of the photos are of the two of us as children. She wants to make sure I include this information in the book, or that ideally, I don’t write it at all. She wants everyone to know that we are, or were, okay. That we had happy childhoods and what happened was a freak event, something unspeakable and private. And I understand that: we all have different ways of processing our grief. My mother believes that my brother has a traumatic brain injury. His MRI, taken in the last year, is clean. Normal, whatever that means. But he was diagnosed with ASPD, or antisocial personality disorder—what we call psychopathy or sociopathy—by two prison psychiatrists.

When I launched my first book, and after, a lot of people asked about my research process in drafting Cost of Living. There was a certain degree of interest in this, mostly from other writers. I must be doing deep dives into certain kinds of material; how else could I remember an event or some small detail? Didn’t I love the research? Didn’t I get hung up on research? Use research as a distraction and read many books? No. I do not. Mostly, I just wait for someone to mail me something. And I read, mostly novels.

There are other ways of doing research, sure. I spend a lot of time on Google Maps, inching forward and backward through time. I FOIA things, poorly, and the county sheriff sends me pages and pages of nothing but redactions. I dabble in the tax records, or the county courthouse records, but mostly for context. When it comes to the actual thing I am looking for, I probably already have it, because I obsessively journaled for many years, or else kept the original receipts, some scrap of paper, medical records, or a screenshot of a text message. I’m all about obsessive documentation for reasons I can’t really explain. I think part of it is because I feel like I am often misunderstood, and I need additional evidence to explain my point of view. This is, I know, related to my nonverbal learning disability, the developmental disability I have similar to autism. For many years, I filled several pages with the minutiae of my day, combined with endless to-do lists and little scenes of experiences immediately after they occurred. Now I keep two kinds of journals—one is all material for the book. The other, my feelings about the book. The B side, I tell people, as if I am transcribing on vinyl or cassette. Mostly in the B-side journal I am very angry, or sad.

By contrast, when I think of research, I am not terribly interested in the sort of history books that many narrative nonfiction writers often make. I can read their book and learn things, but also, if they are writing a memoir in addition to this research, using their lived experience to prop up the investigation, I immediately think: no thank you. A lot of these kinds of books mostly travel in the same sets of facts, particularly about health and illness. Mostly it comes from the fact that a lot of these books are “researched” but a lot of the research is light, because in some cases the author does not know how to do research. I do not want to hear skimmed-over health facts amalgamated from many sources of varying repute. If your book has foot or endnotes and is intended for the general reading public, and you are not an expert in your field, I am probably not interested. Which is why I read a lot of novels, or poetry, instead, where the research is done, but implicit, rather than explicit. I think explicit is what people think of when they talk about research in nonfiction. I do not want to read ten pages from ten different books and weave these facts into a narrative. I cannot write a five paragraph essay to save my life, and a lot of these books involve this kind of transcription. I am more interested in the prose, the way the story is told, rather than the facts themselves. Even though I have read some books while trying to understand how we got here, why my brother burned my parents’ house to the ground, why he doesn’t seem to have any remorse for what he did, how he saved his photo album from childhood before setting the house on fire, mostly photos of him at T-ball and Little League, then later, on a skateboard—I will likely not quote any of those books in this book. It’s just not for me. I am looking for a narrative that feels like a continuous dream, and too many outside facts are just a distraction.

Reading and enjoying lately:

-Ori Fienberg, my incredible spouse, has a new micro-chap about bureaucracy, climate anxiety, horses, pie, and many other things, titled Interim Assistant Dean of Having a Rich Inner Life, downloadable for free from Ghost City Press and a prose poem in HAD.

-I know I’ve mentioned it in an earlier post already, but Lillian-Yvonne Bertram’s Negative Money is out now and you should buy it. Recently, there was some nonsense of about their work after they won the New Michigan Press chapbook prize (again, might I add! How Narrow My Escapes is brilliant), where (mostly white women) writers failed to recognize that Bertram has been working using large language models for a long time, and these writers believed that their work was an “AI chapbook.” To be reduced to that sort of descriptor really indicates how little they know about LYB’s work and how they construct these poems. If you are new to their work, you might start with Travesty Generator, which was longlisted for the National Book Award.

-I am finally playing Stardew Valley, on an Xbox One. Let me know if you want to play in a co-op. I am on Central Time.